What does the term marketing mean? Many people think of marketing only as selling and advertising. It is no wonder—every day we are bombarded with television commercials, newspaper ads, direct-mail campaigns, and sales calls. However, selling and advertising are only the tip of the marketing iceberg. Although they are important, they are only two of many marketing functions and are often not the most important ones.

What does the term marketing mean? Many people think of marketing only as selling and advertising. It is no wonder—every day we are bombarded with television commercials, newspaper ads, direct-mail campaigns, and sales calls. However, selling and advertising are only the tip of the marketing iceberg. Although they are important, they are only two of many marketing functions and are often not the most important ones.

Today, marketing must be understood not in the old sense of making a sale—"telling and selling"—but in the new sense of satisfying customer needs.

Selling occurs only after a product is produced. By contrast, marketing starts long before a company has a product.

Marketing is the homework that managers undertake to assess needs, measure their extent and intensity, and determine whether a profitable opportunity exists.

Marketing continues throughout the product's life, trying to find new customers and keep current customers by improving product appeal and performance, learning from product sales results, and managing repeat performance. If the marketer does a good job of understanding consumer needs, develops products that provide superior value, and prices, distributes, and promotes them effectively, these products will sell very easily.

We define marketing as a social and managerial process whereby individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others.

Figure 1.1 shows that these core marketing concepts are linked, with each concept building on the one before it.

Needs, Wants, and Demands

Human needs are states of felt deprivation. They include basic physical needs for food, clothing, warmth, and safety; social needs for belonging and affection; and individual needs for knowledge and self-expression. These needs were NOT invented by marketers; they are a basic part of the human makeup.

Wants are the form human needs take as they are shaped by culture and individual personality. An American needs food but wants a hamburger, French fries, and a soft drink. A person in Mauritius needs food but wants a mango, rice, lentils, and beans. Wants are shaped by one's society and are described in terms of objects that will satisfy needs.

People have almost unlimited wants but limited resources. Thus, they want to choose products that provide the most value and satisfaction for their money.

When backed by buying power, wants become demands. Consumers view products as bundles of benefits and choose products that give them the best bundle for their money. A Honda Civic means basic transportation, affordable price, and fuel economy; a Lexus means comfort, luxury, and status. Given their wants and resources, people demand products with the benefits that add up to the most satisfaction.

Products and Services

People satisfy their needs and wants with products and services. A product is anything that can be offered to a market to satisfy a need or want. The concept of product is not limited to physical objects—anything capable of satisfying a need can be called a product. In addition to tangible goods, products include services, which are activities or benefits offered for sale that are essentially intangible and do not result in the ownership of anything. Examples include banking, airline, hotel, tax preparation, and home repair services.

More broadly defined, products also include other entities such as service, experiences, properties, persons, places, organizations, information, and ideas.

Many sellers make the mistake of paying more attention to the specific products they offer than to the benefits produced by these products. They see themselves as selling a product rather than providing a solution to a need. A manufacturer of drill bits may think that the customer needs a drill bit, but what the customer really needs is a hole. These sellers may suffer from "marketing myopia"… ( please read the next article about Marketing Myopia,I have another point of view-Amira)—they are so taken with their products that they focus only on existing wants and lose sight of underlying customer needs. They forget that a product is only a tool to solve a consumer problem. These sellers will have trouble if a new product comes along that serves the customer's need better or less expensively. The customer with the same need will want the new product.

Value, Satisfaction, and Quality

Consumers usually face a broad array of products and services that might satisfy a given need. How do they choose among these many products and services? Consumers make buying choices based on their perceptions of the value that various products and services deliver.

Customer value is the difference between the benefits the customer gains from owning and using a product and the costs of obtaining the product. For example, FedEx customers gain a number of benefits. The most obvious are fast and reliable package delivery. However, when using FedEx, customers also may receive some status and image values. Using FedEx usually makes both the package sender and the receiver feel more important. When deciding whether to send a package via FedEx, customers will weigh these and other values against the money, effort, and psychic costs of using the service. Moreover, they will compare the value of using FedEx against the value of using other shippers—UPS, Airborne, the U.S. Postal Service—and select the one that gives them the greatest delivered value.

Customers often do not judge product values and costs accurately or objectively. They act on perceived value. For example, does FedEx really provide faster, more reliable delivery? If so, is this better service worth the higher prices FedEx charges? The U.S. Postal Service argues that its express service is comparable, and its prices are much lower. However, judging by market share, most consumers perceive otherwise. FedEx dominates with more than a 45 percent share of the U.S. express-delivery market, compared with the U.S. Postal Service's 8 percent. The Postal Service's challenge is to change these customer value perceptions.

Customer satisfaction depends on a product's perceived performance in delivering value relative to a buyer's expectations. If the product's performance falls short of the customer's expectations, the buyer is dissatisfied. If performance matches expectations, the buyer is satisfied. If performance exceeds expectations, the buyer is delighted.

Outstanding marketing companies go out of their way to keep their customers satisfied. Satisfied customers make repeat purchases, and they tell others about their good experiences with the product. The key is to match customer expectations with company performance. Smart companies aim to delight customers by promising only what they can deliver, then delivering more than they promise.

Customer satisfaction is closely linked to quality. In recent years, many companies have adopted total quality management (TQM) programs, designed to constantly improve the quality of their products, services, and marketing processes. Quality has a direct impact on product performance and hence on customer satisfaction.

In the narrowest sense, quality can be defined as "freedom from defects." But most customer-centered companies go beyond this narrow definition of quality. Instead, they define quality in terms of customer satisfaction. For example, the vice president of quality at Motorola, a company that pioneered total quality efforts in the United States, says that "Quality has to do something for the customer. . . . Our definition of a defect is 'if the customer doesn't like it, it's a defect.' " Similarly, the American Society for Quality Control defines quality as the totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy customer needs. These customer-focused definitions suggest that a company has achieved total quality only when its products or services meet or exceed customer expectations. Thus, the fundamental aim of today's total quality movement has become total customer satisfaction. Quality begins with customer needs and ends with customer satisfaction.

Exchange and Relationships

Marketing occurs when people decide to satisfy needs and wants through exchange. Exchange is the act of obtaining a desired object from someone by offering something in return. Exchange is only one of many ways that people can obtain a desired object. For example, hungry people could find food by hunting, fishing, or gathering fruit. They could beg for food or take food from someone else. Or they could offer money, another good, or a service in return for food.

As a means of satisfying needs, exchange has much in its favor. People do not have to prey on others or depend on donations, nor must they possess the skills to produce every necessity for themselves. They can concentrate on making things that they are good at making and trade them for needed items made by others. Thus, exchange allows a society to produce much more than it would with any alternative system.

In the broadest sense, the marketer tries to bring about a response to some offer. The response may be more than simply buying or trading goods and services. A political candidate, for instance, wants votes and a social action group wants idea acceptance. Marketing consists of actions taken to obtain a desired response from a target audience toward some product, service, idea, or other object.

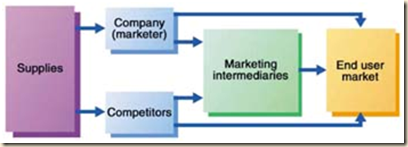

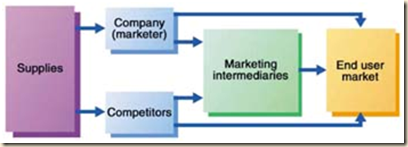

Marketers need to build long-term relationships with valued customers, distributors, dealers, and suppliers. They want to build strong economic and social connections by promising and consistently delivering high-quality products, good service, and fair prices. Increasingly, marketing is shifting from trying to maximize the profit on each individual transaction to building mutually beneficial relationships with consumers and other parties. In fact, ultimately, a company wants to build a unique company asset called a marketing network. A marketing network consists of the company and all its supporting stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, distributors, retailers, ad agencies, and others with whom it has built mutually profitable business relationships. Increasingly, competition is not between companies but rather between whole networks, with the prize going to the company that has built the better network. The operating principle is simple: Build a good network of relationships with key stakeholders and profits will follow.

Markets

A market is the set of actual and potential buyers of a product. These buyers share a particular need or want that can be satisfied through exchanges and relationships.

Thus, the size of a market depends on the number of people who exhibit the need, have resources to engage in exchange, and are willing to offer these resources in exchange for what they want.

Producers go to resource markets (raw material markets, labor markets, money markets), buy resources, turn them into goods and services, and sell them to intermediaries, who sell them to consumers. The consumers sell their labor, for which they receive income to pay for the goods and services that they buy. The government is another market that plays several roles. It buys goods from resource, producer, and intermediary markets; it pays them; it taxes these markets (including consumer markets); and it returns needed public services. Thus, each nation's economy and the whole world economy consist of complex, interacting sets of markets that are linked through exchange processes.

Demand Management

Some people think of marketing management as finding enough customers for the company's current output but this view is too limited. The organization has a desired level of demand for its products. At any point in time, there may be no demand, adequate demand, irregular demand, or too much demand, and marketing management must find ways to deal with these different demand states. Marketing management is concerned not only with finding and increasing demand but also with changing or even reducing it.

For example, the Golden Gate Bridge sometimes carries an unsafe level of traffic, and Yosemite National Park is badly overcrowded in the summer. Power companies sometimes have trouble meeting demand during peak usage periods. In these and other cases of excess demand, demarketing may be required to reduce demand temporarily or permanently. The aim of demarketing is not to destroy demand but only to reduce or shift it. Thus, marketing management seeks to affect the level, timing, and nature of demand in a way that helps the organization achieve its objectives. Simply put, marketing management is demand management.

Building Profitable Customer Relationships

Managing demand means managing customers. A company's demand comes from two groups: new customers and repeat customers. Traditionally, marketers have focused on attracting new customers and creating transactions with them. In today's marketing environment, however, changing demographic, economic, and competitive factors mean that there are fewer new customers to go around. The costs of attracting new customers are rising. Thus, although finding new customers remains very important, the emphasis is shifting toward retaining profitable customers and building lasting relationships with them.

Companies have also discovered that losing a customer means losing not just a single sale but also a lifetime's worth of purchases and referrals. For example, the customer lifetime value of a Taco Bell customer exceeds $12,000. For Lexus, one satisfied customer is worth $600,000 in lifetime purchases. Thus, working to keep profitable customers makes good economic sense. The key to customer retention is superior customer value and satisfaction. With this in mind, many companies are going to extremes to keep their customers satisfied.

Marketing Challenges in the New "Connected" Millennium

As the world spins into the first decade of the twenty-first century, dramatic changes are occurring in the marketing arena. Richard Love of Hewlett-Packard observes, "The pace of change is so rapid that the ability to change has now become a competitive advantage." Yogi Berra, the legendary New York Yankees catcher, summed it up more simply when he said, "The future ain't what it used to be." Technological advances, rapid globalization, and continuing social and economic shifts—all are causing profound changes in the marketplace. As the marketplace changes, so must those who serve it.

The major marketing developments today can be summed up in a single theme: connectedness. Now, more than ever before, we are all connected to each other and to things near and far in the world around us. Moreover, we are connecting in new and different ways. Where it once took weeks or months to travel across the United States, we can now travel around the globe in only hours or days. Where it once took days or even weeks to receive news about important world events, we now see them as they are occurring through live satellite broadcasts. Where it once took days or weeks to correspond with others in distant places, they are now only moments away by phone or the Internet.

Through electronic commerce, customers can design, order, and pay for products and services without ever leaving home. Then, through the marvels of express delivery, they can receive their purchases in less than 24 hours.

From virtual reality displays that test new products to online virtual stores that sell them, the boom in computer, information, telecommunication, and transportation technology is affecting every aspect of marketing. Consider the rapidly changing face of personal selling. Many companies now equip their salespeople with the latest sales automation tools, including the capacity to develop individualized multimedia presentations and to develop customized market offerings and contracts. Many buyers now prefer to meet salespeople on their computer screens rather than in the office. An increasing amount of personal selling is occurring through videoconferences or live Internet presentations, where buyers and sellers can interact across great distances without the time, costs, or delays of travel.

Companies of all types are now attempting to snare new customers on the Web. Many traditional "brick-and-mortar" companies have now ventured online in an effort to snare new customers and build stronger customer relationships. For example:

- Car makers such as Toyota use the Internet to develop relationships with owners as well as to sell cars. Its site offers product information, dealer services and locations, leasing information, and much more. For example, visitors to the site can view any of seven lifestyle magazines—alt.Terrain, A Man's Life, Women's Web Weekly, Sportzine, Living Arts, Living Home, and Car Culture—designed to appeal to Toyota's well-educated, above-average-income target audience.

- Sports fans can cozy up with Nike by logging onto Nike.com, where they can check out the latest Nike products, explore the company's history, or download their favorite athlete's stats. Through its Web page, in addition to its mass-media presence, Nike relates with customers in a more personal, one-to-one way.

The Internet has also spawned an entirely new breed of companies—the so-called "dot coms"—which operate only online. For example:

Fast-growing eToys is quickly becoming an indispensable ally to time-starved parents looking for a fast and convenient way to buy toys for their children. The three-year-old Web-only retailer pioneered in selling everything from teddy bears to Barbies online. Now the site offers more than 100,000 toys, books, software, videos, and other kid items. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, shoppers can click onto eToys, search for a specific item or browse one of several categories, drop their selections into a virtual shopping cart, pay for them with a credit card, and have them delivered within a day or two by express shipping. The eToys Web site also offers recommendations by age groups, a gift registry, a bestsellers list, and features on the latest children's products. Is the site successful? After only three years, eToys has won some 600,000 customers and almost $30 million of their purchases. "There is tremendous competition," says eToys CEO Toby Lenk. "The difference is we are just kids and we are just the Web."

Thus, changes in connecting technologies are providing exciting new opportunities for marketers. We now look at the ways these changes are affecting how companies connect with their customers, marketing partners, and the world around us

Connections with Customers

The most profound new developments in marketing involve the ways in which today's companies are connecting with their customers. Yesterday's companies focused on mass marketing to all comers at arm's length. Today's companies are selecting their customers more carefully and building more lasting and direct relationships with these carefully targeted customers.

Connecting for a Customer's Lifetime

At the same time that companies are being more selective about which customers they choose to serve, they are serving those they choose in a deeper, more lasting way. In the past, many companies have focused on finding new customers for their products and closing sales with them. In recent years, this focus has shifted toward keeping current customers and building lasting relationships based on superior customer satisfaction and value. Increasingly, the goal is shifting from making a profit on each sale to making long-term profits by managing the lifetime value of a customer.

For example, Amazon.com

began as an online bookseller, but now offers music, videos, gifts, toys, consumer electronics, home improvement items, and even an online auction as well, increasing per-customer sales. In addition, based on each customer's purchase history, the company recommends related books, CDs, or videos that might be of interest. In this way, Amazon.com captures a greater share of each customer's leisure and entertainment budget.

began as an online bookseller, but now offers music, videos, gifts, toys, consumer electronics, home improvement items, and even an online auction as well, increasing per-customer sales. In addition, based on each customer's purchase history, the company recommends related books, CDs, or videos that might be of interest. In this way, Amazon.com captures a greater share of each customer's leisure and entertainment budget.

Connecting Directly

Today, beyond connecting more deeply, many companies are also taking advantage of new technologies that let them connect more directly with their customers. In fact, direct marketing is booming. Virtually all products are now available without going to a store—by telephone, mail-order catalogs, kiosks, and electronic commerce.

Some companies sell only via direct channels—firms such as Dell Computer , Lands' End,

, Lands' End,  1-800-Flowers, and Amazon.com,

1-800-Flowers, and Amazon.com,

to name only a few. Other companies use direct connections as a supplement to their other communications and distribution channels. For example, Procter & Gamble sells Pampers disposable diapers through retailers, supported by millions of dollars of mass-media advertising. However, P&G uses its Web site to build relationships with young parents by providing information and advice on everything from diapering to baby care and child development. Similarly, you can't buy crayons from the Crayola Web site. However, you can find out how to remove crayon marks from your prize carpeting or freshly painted walls.

Connections with Marketing Partners

In these ever more connected times, major changes are occurring in how marketers connect with others inside and outside the company to jointly bring greater value to customers.

Companies need to give careful thought to finding partners who might complement their strengths and offset their weaknesses. Well-managed alliances can have a huge impact on sales and profits.

Connections with Our Values and Social Responsibilities

Marketers are reexamining their connections with social values and responsibilities and with the very Earth that sustains us.

As the worldwide consumerism and environmentalism movements mature, today's marketers are being called upon to take greater responsibility for the social and environmental impact of their actions.

Corporate ethics and social responsibility have become hot topics in almost every business arena, from the corporate boardroom to the business school classroom.

And few companies can ignore the renewed and very demanding environmental movement.

================

“Principles of Marketing”- Kotler&Armstrong-Chapter.1